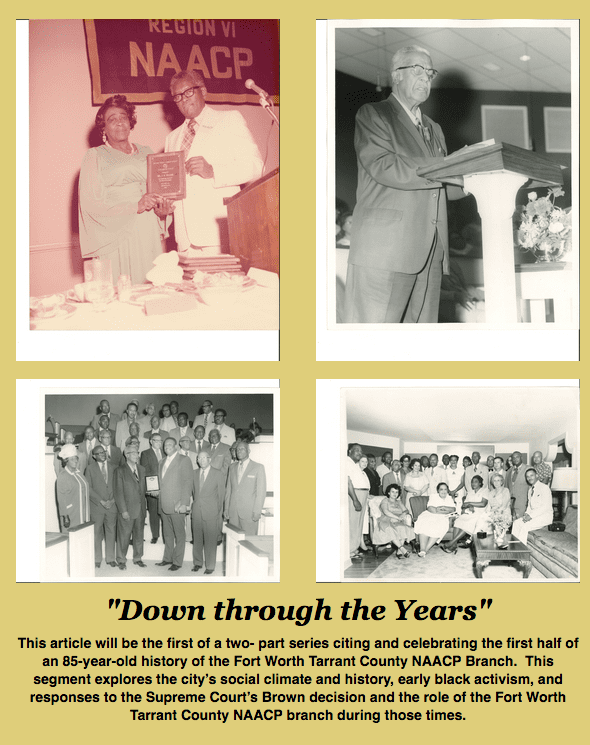

In Celebration of 85 Years

This article will be the first of a two- part series citing and celebrating the first half of an 85-year-old history of the Fort Worth Tarrant County NAACP Branch. This segment explores the city’s social climate and history, early black activism, and responses to the Supreme Court’s Brown decision and the role of the Fort Worth Tarrant County NAACP branch during those times.

Early activities of the NAACP Fort Worth Tarrant County Branch were varied but the most significant issue was its history, effectiveness of, and response to court-ordered integration. In the early days, Texas branches were frequent litigants in school desegregation and legislative redistricting cases and the Fort Worth Tarrant County Branch was no exception.

By the time of the 1954 Brown decision, the schools for African Americans remained separate and inferior in physical structure, student to teacher ratio, and funding allocation. African Americans living in Fort Worth sought to address that inequality as well as to demand their equal rights in other areas. El Paso residents established the first Texas branch of the NAACP in 1915. Four other cities, including Fort Worth, applied for charters in the following years.

The Branch was chartered on July 9, 1934. While the Brown decision brought the most visible activism in Fort Worth’s black community, local African Americans made their voices heard in Fort Worth years before the Brown decision, particularly through NAACP membership and activism.

Although the Supreme Court decided Brown in 1954, Fort Worth school officials made little noise and no movement towards integration. Things reached a boiling point in 1955, when the Southwest Regional Branch of the NAACP reinforced its pressure on Texas’ government to support integration. U. Simpson Tate of the Southwest Regional Counsel visited Fort Worth in August of that year and met with FWISD’s superintendent.

Tate summarized the meeting by stating, “The sum and substance of the meeting was a clear expression that at present the Fort Worth Independent School District has no plans for integration . . . Actually, it is doing nothing but marking time.” He concluded by stating, “It is very likely that a suit will have to be filed against this board very soon.”

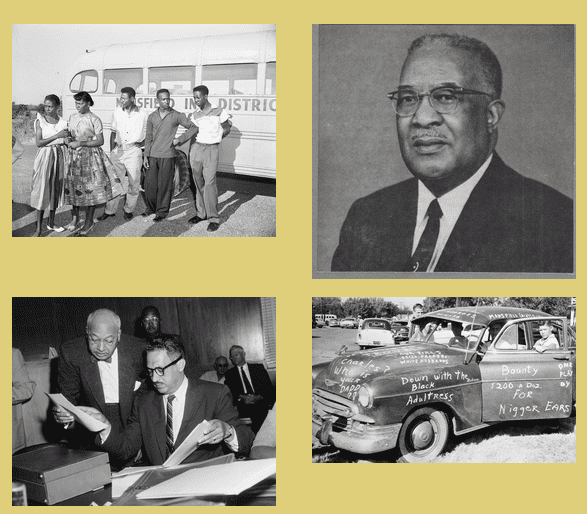

During the 1954-55 academic year, three male African American students, Floyd Moody, Nathaniel Jackson, and Charles Moody, attempted to enroll at Mansfield High School. The school denied them admission, and their parents filed suit against the Mansfield Independent School District. T.M. Moody, president of the Mansfield branch of the NAACP, John F. Lawson, Southwest Regional Counsel, U. Simpson Tate, and W.J. Durham, NAACP Texas state special counsel, represented the plaintiffs. The group asked newly arrived and NAACP Counsel, L. Clifford Davis to assist with the case. Davis filed a class-action suit on October 7, 1955 in Fort Worth’s federal district court. Davis had moved from Arkansas, where he practiced “equalization lawsuits,” to Texas, where he served as lead counsel on civil rights cases in Fort Worth and Mansfield for the NAACP.

The two fathers worked in conjunction with the local NAACP to challenge segregation, arguing that the district’s refusal to integrate the public schools violated their children’s constitutional rights as defined in Brown. In response, the local NAACP, represented by Fort Worth attorney L. Clifford Davis, filed suit against the district in November. His involvement in legal challenges became an integral part of the branch’s activities to break through segregation.

Only two months later, members of the local NAACP and African American residents of Mansfield, Texas, filed an integration suit in Fort Worth challenging school segregation. When a federal court ordered Mansfield High School to desegregate in Jackson v. Rawdon, then governor Allan Shivers sent the Texas Rangers to prevent integration. Governor Shivers filed an injunction against the NAACP for violating the state’s barratry laws which in turn meant the NAACP could not continue to do business in Texas.

A Dallas editorialist, Lynn Landrum, wrote a Thinking Out Loud piece titled “Their Right of Petition.” The article summarized her opinion that “Persecution of members of NAACP does not appeal to the writer as a fair or profitable fashion in which to oppose the program of that organization. We have to keep reminding ourselves that colored people have the right of petition the same as other people.” But while many white Texans opposed the organization, at least some supported its right to freely operate.

NAACP Executive Secretary Roy Wilkins responded to the column in a letter to the Dallas Morning News. He denied the timeworn allegations that the NAACP was subversive and had Communist ties. Wilkins wrote, “Unhappily, by one vote, the Texas legislature has passed a bill requiring the filing of membership lists by the NAACP. We hoped that the Texas tradition of hard, but fair, play would have caused your great state to join Florida and North Carolina in reversing a foolish trend.”

On May 8, 1957, at 2 p.m., Judge Otis T. Dunagan found the case against the NAACP groundless, allowing the NAACP to resume activities in Texas.

Then branch president, Dr. George D. Flemmings, continued to be vocal about the school board’s rationale of blocking integration. “The school board is violating the law and they’ll find out – very soon, I hope,” Flemmings told the Star-Telegram,” expressing the NAACP’s intentions to move forward.

The 1957-58 academic school year in Fort Worth opened segregated as usual.

The local NAACP branch responded by mailing a letter to parents of African American children, urging parents to enroll their children in “the best school and the school nearest their homes and most convenient to them.” Flemmings, the letter’s author, informed parents “in the event any qualified student is denied enrollment at any public school in Fort Worth, please call and report the details.

Executive Order 9981 had been issued by President Harry Truman in 1948 which effectively desegregated the armed forces of the United States. One beneficiary of Truman’s order was Technical Sergeant Weirleis Flax, Sr. who had relocated to live on Carswell Air Force base in Fort Worth from Wichita Falls where his children had attended integrated schools on base; Carswell lacked a school for servicemen’s families, so they sent their children to local Fort Worth schools. On September 8, 1959, Flax escorted six-year-old Arlene to nearby Burton Hill Elementary, a white school that her friends living on base attended and attempted to enroll her there. The principal denied her entry to Burton Hill, informing Flax that under Fort Worth’s segregated school system, Arlene would ride the bus to all-black Como Elementary, roughly twice the distance from Carswell than to Burton Hill.

The same day, Herbert Teal, a father of six, attempted to register his children at all-white Peter Smith Elementary School, only to meet with rejection by the school’s principal. Flax, who surely found his new life in a Jim Crow environment insulting, met with Teal, a local activist. Both men filed a class action suit against the school board on behalf of their children and all other African American children in Fort Worth. In response, the local NAACP, represented by Fort Worth attorney L. Clifford Davis, filed suit against the district in November.

Despite the obvious attempts by the school board to avoid integration, Fort Worth’s African American citizens maintained their quest for equality and on December 14, 1961, Judge Brewster, citing the Brown decision, declared Fort Worth’s dual school system unconstitutional.

As with battles over school integration, the debate on integration of public spaces took place on a national level.

African Americans in Fort Worth experienced the indignities of Jim Crow whenever they ventured beyond their black neighborhoods through the 1950s. Stores and restaurants kept strict color lines, and segregation prevented equal access to public spaces. City officials allowed for limited access to public facilities, including the Fort Worth tradition of opening the city zoo and other parks to African Americans on June 19th, or Juneteenth, only.

Rather than quietly accept the limited Juneteenth access to public facilities, the Baptist Ministers Union and the Interdenominational Ministers Alliance urged the African American community to boycott the zoo and Forest Park on June 19, 1953.

In 1955, a group of Como residents had petitioned the council for a pool in their neighborhood, but the board had wavered on and then ignored this request until the NAACP attorney demanded integration of all public pools. Instead of fighting over integrated pools, the NAACP Fort Worth branch narrowed its focus to the Flax case. Instead of swimming in pools with the supervision of a lifeguard, children instead would swim in natural waterways, which would increase the risk of drowning. Rather than leave the pools closed, Holland argued, the city should build a pool in the Como area. The local NAACP exercised the adage of picking its battles when it came to complete integration of public places. Even though the attorneys threatened a lawsuit, the segregated swimming pools remained largely unchallenged until 1964.

The decision to go outside of the designated African American neighborhoods for housing put many African Americans in harm’s way. In September 1954 Jet Magazine reported a dynamite blast destroyed a car belonging to Fort Worth, Texas, high school teacher Kerven W. Carter, Jr. whose parents had recently moved next door to two white families in suburban Riverside. Carter’s car was ruined and his home damaged while he, his wife, and three-year-old son slept inside. Carter, who lived in Lake Como, said white neighbors of his parents, Mr. and Mrs. K.W. Carter, Sr., had twice told him: “You’d better stay out of this neighborhood.”

Lloyd G. Austin, an African American, bought a house on Judkins Avenue in September 1956 in the predominately white Morningside neighborhood and experienced threats and a riot outside his newly purchased home.

African American attorney L. Clifford Davis, who represented the NAACP in the Mansfield and Flax cases, supported Austin. After a group of angry white rioters became aggressive, Davis warned that Austin, and other African Americans, had the right to defend themselves. Afterwards the police arrived and eventually dispersed the crowd of about 200 white adults and teen-agers.

A prominent example of voluntary integration occurred in the Leonard Department Store. Marvin Leonard founded the Leonard Bros. Department Store in Fort Worth. Rather than isolate his predominately African American customer base, the department store owner integrated the rest rooms, lunch counters, and water fountains by 1956.

In the months before the Civil Rights Act’s passage, citizens were hard at work attacking the old system. Local civil rights leader Dr. Marion J. Brooks led a group of one hundred African American activists to the state capital in Austin, Texas, to protest state-mandated public accommodation laws. Lenora Rolla, a long-time Fort Worth activist and founder of the Tarrant County Black Historical and Genealogical Society, reflected on her involvement in Alabama and Mississippi demonstrations, but claimed, “We had our little movement right here in Fort Worth.” According to Rolla, “We had sit-ins at the bus station because they wouldn’t let black people eat there. They refused to serve us, so we sat there.”

Some of the noted successes during the early years of NAACP history include:

In 1959, the Fort Worth district attorney’s office hired the city’s first African American assistant district attorney, Ollice Malloy.

In 1963, the district attorney later hired two African American women to work in the office

In March of 1964, the city hired its first “Negro ‘White Collar’ Help.” Vera Jenkins worked as a typist in the corporation court office while Ethel Hall typed and filed for the Warrant Division. Both Jenkins and Hall graduated from I.M. Terrell High School.

In light of those successes, Fort Worth’s NAACP branch still actively participated in championing local civil rights. By May 1964, Fort Worth NAACP members had contributed $1,000 to the NAACP’s Freedom Fund. The four churches leading the drive included Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church, Greater St. James Baptist Church, Mount Gilead Baptist Church, and Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church. Two years later, the Fort Worth NAACP branch again reached its goal of $1,005 for the Freedom Fund.

On behalf of the local NAACP, Dr. George D. Flemmings in 1964 submitted a request to Board of Education President Atwood McDonald asking for a complete integration of all school grades for the 1964-65 school year. Complete integration came in 1967.

In 1970, the Fort Worth NAACP again petitioned the court, opposing the proposed construction of Morningside High School. The NAACP claimed the school would foster segregation, because the district planned the construction in a predominantly black neighborhood. Again, the NAACP and the district’s attorneys returned to court.

Fort Worth’s NAACP branch remained active and grew throughout the 1960s. A 1964 newsletter reported that although the national office set a quota of 1,500 Fort Worth members, the local branch exceeded that allocation, the first major branch in the southwest region to do so. In May 1964, Fort Worth NAACP president Flemmings reported that 1,672 people applied for membership in the Fort Worth NAACP branch. An article detailing the excess membership also listed the four church congregations leading the membership drive. Those include Reverend S.T. Alexander’s Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church, C.A. Holliday of Greater St. James Baptist Church, Mount Gilead Baptist Church and Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church, guided by C.C. Harper and A.E. Chew respectively.

The local NAACP and the powerful church leadership would prove indispensable in the fight for civil rights in Fort Worth during the 1960s through the 70’s. – The End –